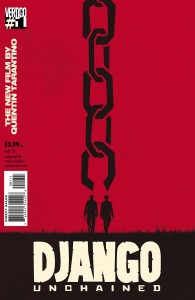

When DC Comics announced at San Diego Comic-Con that they were planning to release a comics adaptation of Quentin Tarantino’s movie Django Unchained, which is out in theaters today, I was not particularly enthusiastic, even though I am a Tarantino fan from years back.

When DC Comics announced at San Diego Comic-Con that they were planning to release a comics adaptation of Quentin Tarantino’s movie Django Unchained, which is out in theaters today, I was not particularly enthusiastic, even though I am a Tarantino fan from years back.

Why? Well, picture the first fifteen minutes of Pulp Fiction. Now try to picture that quarter hour as a comic book. Hell, imagine it as a major event comic with A-list talent; let’s say they got Frank Miller to do the art, because after all, the man knows how to draw people in black and white suits. What do you think that comic book would look like? That’s right: it would be 75 pages long with half of those pages being word balloons. And the visuals would be of three different angles of two guys sitting quietly in a car, giving Miller all kinds of unexpected free time to shriek at hippies to get off his lawn. And we know that those would be some killer word balloons, but as a comic book? Not the most exciting-sounding four-color experience. Frankly, if you pitched a comic issue about two guys in a car talking about cheeseburgers and the metric system without using the name “Tarantino,” even Brian Michael Bendis would say, “Meh; sounds kinda… talky“.

So at first glance, a Tarantino comic sounds like a rough idea on its face. However, Django Unchained is a western, which at least implies a certain amount of action and visual dynamism… but to play Devil’s Advocate, Pulp Fiction was a crime movie, which would also imply some adrenaline pounding, but which really only would provided it during the, well, adrenaline pounding. So how does this comic play? An ultra-literate Jonah Hex shoot ’em up? Or, to paraphrase Eric Cartman: a couple of gay cowboys talking about pudding?

Django Unchained opens in Texas during the 1800s with a group of horsemen driving a group of slaves across the landscape, when they are interrupted by Dr. King Schultz (and his horse Frtiz, as he seems compelled to introduce the horse to all comers), former dentist and current bounty hunter, who is looking to obtain a slave who was previously owned by the Carrucan Plantation and therefore might be able to identify that farm’s former overseers, who have paper out on them. Enter Django, who claims he can point them out, leading Schultz to make an offer to buy Django on the spot: 120 dollars, and one bullet, with the implication that the second round of negotiations will include much more lead. Schultz then spends time educating Django on the ways of the bounty hunter, and makes Django an offer: help Schultz find the Brittle Brothers and earn his own freedom.

Let’s kick off the the obvious: this book is based on not only a Tarantino script, but on an uncut and unexpurgated version of that script, so this is one talky comic. For example, there’s a two-page spread of Schultz and Django attempting to draw out a bounty that is comprised of 32 word balloons and 12 panels of them heroically and valiantly… entering a saloon and ordering a beer. So be prepared to spend a lot of time, as in Pulp Fiction, watching a couple of guys riding around and talking. Which might sound boring on its face, but let’s remember: these are guys riding around talking, using words written by Quentin Tarantino (there is no credited writer other than Tarantino on the issue, so I’m assuming this dialogue is straight from Tarantino’s original script). So it’s talky, but it’s pretty damn entertaining talk:

Well, what if I say, I don’t like your fancy pants nigger, and I wouldn’t sell you a tinker’s damn – what’cha gotta say about that?

Mr. Bennett, if you are the business man I’ve been led to believe you to be, I have five thousand things I might say that could change your mind.

C’mon inside, get yourself something cool to drink.

And even simple gag lines like:

So you really free?

Yes.

You mean you wanna dress like that?

That’s pretty good stuff… but be forewarned: it is Tarantino stuff, and it is set in the South during slavery, so it is raw. There’s a word up there in that first dialogue quote that you are gonna see a lot in this issue, and if that bothers you, even though its use contextually makes sense within the setting and scope of the story, you are gonna have a problem with this book. I personally didn’t, but I’m a white guy and a Tarantino fan.Your mileage may vary.

Another place you might have a problem is in the story’s pacing, particularly if you’re an action nut, because there really isn’t much. Sure, this is a western and that means gunplay, but while we get a couple of shootings in this issue, there are no gunfights; each shooting is a one or two panel ambush shooting kind of situation, punctuated by big words and florid, stylized conversation. Which, again, is fine if you like Tarantino’s writing… but if you’re the type of guy who hates seeing Bendis do another “dudes talking around a coffee table” scene, you are probably not gonna get into this book. Tarantino movies are about the pop culture references (and when we discovered Django’s wife’s last name, I started wondering when Tarantino planned to reveal that Django’s last name was “Dolemite,” or perhaps, “Superfly”), stylized dialogue and visuals. Heavy action scenes? Well, not so much. At least not yet anyway.

Speaking of visuals, I’m not sure that DC could have done much better than picking R. M. Guera, the artist for Scalped, which is for all intents and purposes a modern western noir, which is as close to a Tarantino-esque western as you’re gonna get. He does a decent job keeping the pace up on these dialogue-heavy scenes by keeping the panel sizes small; other than the first page and one other page, which help to establish new scenes and settings, Guera keeps to a six or seven-panel page to keep things feeling like they’re moving, even when it’s just two dudes talking. His camera moves add some dynamism to what could easily be a five-minute long take in an actual movie, and his facial expressions, figures and backgrounds add a feeling of setting authenticity to the story. Most importantly for an adaptation, Guera doesn’t let himself get hamstrung into making every panel be a photo reference of the actors playing the parts in the movie version. If I had a nickel for every comic based on a movie or TV show that I was dragged out of because the artist tried (and generally failed) to mimic the real actor, I could afford to hire someone else to write this on Christmas. All in all, Guera does good work here, and plays a major part in keeping things moving along and not becoming a dialogue-heavy morass. It’s gotta be tough work, but ge does it damn well.

It occurs to me, as it sometimes does when I’m reviewing a book, that I’ve written a lot of words without actually saying whether or not I liked it. And truth be told? I’m not sure. I like me some Tarantino dialogue, and this comic obviously has it in spades. But that kind of story means that we have a lot of pages of dudes shooting the shit, which doesn’t make for the most exciting comic book in the world. And when you’re halfway through a comic and find yourself muttering, “The artist is keeping the panels small so it at least feels like things are happening. Nice,” it means your seeing the men behind the curtain struggling to make the thing work in a format for which the script was never intended.

But I am, as perviously stated, a Tarantino fan. One who, back in 1994, purchased the script for Pulp Fiction because I liked the dialogue so much. If you’re that kind of person, you’ll get something out of the Django Unchained comic. If not? Well, save yourself $3.99 and take that money to the movies. Rumor is, you can get most of this story at the theater down the street, in the format for which it was originally intended.

Podcast RSS Feed

Podcast RSS Feed iTunes

iTunes Google Play

Google Play Stitcher

Stitcher TuneIn Radio

TuneIn Radio Android

Android Miro Media Player

Miro Media Player Comics Podcast Network

Comics Podcast Network