Editor’s Note: Now watch me kids, when I twist my ring: like magic, we’re at Spoiler King!

Editor’s Note: Now watch me kids, when I twist my ring: like magic, we’re at Spoiler King!

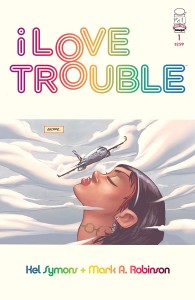

Let’s go ahead and state the obvious up front: I Love Trouble is a superhero comic.

Sure, it’s a superhero comic where the protagonist is a bit darker and edgier than your standard Marvel or DC fare, and it’s one without capes, spandex or superpowered bad guys (yet… unless you count a protagonist who uses her powers to steal classic art a “supervillain” right out of the gate, but the story doesn’t steer in that direction), but there is no way to spin a book about a woman who suddenly develops powers, that forecasts that there are other people out there with similar powers, and that shows government interest in the woman with powers, and see anything but a superhero comic with a darker bend than many.

Our protagonist is Felicia, a New Orleans grifter on the run from Moreaux, a gangster from whom she and her partner conned about 20 large. While on her escape flight to Middle America, her plane goes up in flames, and Felicia learns that she has the power to “bamf” – I mean, “blink” – instantaneously teleport herself for short distances. Using the power to escape the plane crash, she makes her way back home, and sets about using her power to collect enough money (not to mention some original fine art for her own personal collection) to repay Moreaux. Except Moreaux learns about her power, takes her friend Johnny hostage, and demands that Felicia use her power at his behest. Meanwhile, some shady organization has Felicia under surveillance, debating whether or not to approach her…

There is a lot going on in this book that is effective, mostly surrounding Felicia. It is a dicey proposition for a writer to create a protagonist who is a grifter and a sneak thief, and yet one who you hope doesn’t get her head blown off by the people she’s ripped off. And writer Kel Symons handles that tightrope walk effectively, through a combination of her depiction of Felicia, and her depiction of Moreaux and his associates. Symons give Felicia a certain amount of apparent honor and class; if you have a character on the run who has been declared dead, I suppose it takes a certain amount of personal integrity to return to the scene of the crime to make good on the theft when you could always just disappear into the woodwork… although Symons writes the character with enough ambiguity to make it very possible that she is just taking advantage of her new-found opportunity to make a lot of money quick to buy her way out of the problem. In addition, adding the quirk that Felicia is stealing priceless art for her own personal appreciation adds some depth to Felicia’s character, implying that she is more than a simple street hustler who otherwise might have been pulling the short con with Bubbles from The Wire in exchange for crystal meth. All in all, it adds up to a somewhat more complex character than you’d expect from a thief who suddenly gained the power to become, for all intents and purposes, Nightcrawler Catwoman.

Symons helps make Felicia more sympathetic by making Moreaux and his people real fucking scumbags. The problem is that they are not particularly multi-dimensional scumbags; the family’s patriarch is a bloated, man-titted manatee who likes to beat whores while watching TV, and Symons depicts the people around as reacting to the situation negatively only due to the stains the beatings leave. Moreaux himself isn’t much better, shown only as a slightly more articulate douche who we know is deadly simply due to the jailhouse teardrop tattoo on his face. These characters are so broadly drawn that I can’t believe they are meant to be a major part of the story, but they do serve their purpose in raising sympathy toward sneak-thief Felicia; after all, it’s easy to overlook that someone might be a day overdue for a shower when they’re standing next to people who are busily shitting their pants.

The tricky part of this story is in the plot, for a couple of reasons. For example, when you stick a character with the ability to apparently teleport just about anywhere, and come back with anything almost instantaneously, into a life-threatening conundrum like Moreaux’s extortion and eventual hostage-taking, is that you start thinking about what you would do in that situation, and almost anything a writer thinks of isn’t gonna make the grade. Symons has Felicia stand there and let Moreaux’s goon wave his gun around while Moreaux demands Felicia’s services… and all I can think of is ways that you could use instantaneous teleportation (it’s called “blink” after all; this does not imply a slow process) to not only diffuse the situation, but shut the prick down entirely. Such as (and this is entirely off the top of my head):

- Tell Moreaux if he doesn’t cut the shit, you’ll be using your power to deposit ten pounds of Peruvian flake cocaine into his car / house / workplace / asshole and drop the dime to the cops.

- Remind Moreaux that, even if he shoots Johnny, he will be unlikely to shoot the teleporter, who can be at a phone telling the police about the homicide victim at 1010 Tattooed Cocksucker Drive before the gunshot stops resonating.

- We’ve seen Felicia do some real ninja shit with her powers when she steals art, so… go grab the fucking gun.

- We’ve seen Johnny cheating on Felicia (and so has Felicia), so why not just say, “Go ahead, shoot him. I will disappear long before you can shoot me… and I will allow you to guess where and when I will reappear with two hand grenades.”

- Remind Moreaux that she can teleport anyone to anywhere she can see… and tell him that the moon is looking awful bright tonight.

And therein lies the biggest problem with the book: inconsistencies that exist apparently to serve the plot. We have Felicia almost immediately able to use her power well enough to lift money from a diner’s till literally minutes after accidentally discovering her power. We see her making short work of a security guard in an art museum in broad daylight… and yet she appears dumbstruck and powerless over some local hood with a couple of goons. It feels less like a real and tense situation than one required by the plot to put Felicia into distress, so that when the organization that has her under surveillance inevitably approach her in a future issue, she is more likely to be amenable to whatever they offer. Now, that is purely speculation… but the scene sticks out in its incongruity from Felicia’s prior rapid comfort with her power to the point that it is almost obviously a plot device.

And then there was the one little thing that kept bothering me, even after I finished the book: if Felicia’s buddy Johnny is, in fact, the “Tweety” with whom Felicia conned Moreaux (it’s not clear if he is or not, but no other friends or accomplices other than an unnamed estranged family member are mentioned in this issue), why didn’t Moreaux go after him for revenge after Felicia bolted? It made me, and continues to make me, stop and wonder if Johnny and Tweety are one and the same or not, and it is a simple thing that could have been easily clarified: if Johnny’s Tweety, have someone call him that. If he’s not, have him refer to Tweety somehow. It’s a small thing, but it bothered me, and it’s an open question that could have been easily resolved, or made clear that it should be an open question.

Mark A. Robinson’s art is interesting, in that it is a mix of styles I both like and hate. His work appears to be strongly influenced by manga; everyone has big old round eyes, with angular bodies that more than once defy basic biology. Normally I dislike manga-styled art, but everything is cut with a clear Sam Kieth influence; all Robinson’s heads are elongated, with liberal use of plain-English “sound” captions to indicate small action, and little zoom bubbles to accentuate details in the background. Even his female figures are reminiscent of Kieth, with big hips, size-zero waists, and a lot of arched backs. The mix actually makes some sense once you see it, and the coloring by Paul Little, which uses somewhat dull colors, prevents the style from becoming candy-colored anime. Everything hangs together better than it should to the eye of a guy like me, who flatly dislikes manga-looking pencils.

There’s some good stuff to like in I Love Trouble #1, most of it surrounding the book’s protagonist, who is darker than you’d usually expect from a superhero story, if somewhat apparently willfully slow in order to keep the plot moving forward. And the idea that this little story is happening in a world where things could break to a more large-scale superhero story, albeit one with a slightly off-center point of view, is enough to get be to check out another issue. But there are a couple of areas where Felicia acts in a way that just makes the story and plot scaffolding behind the curtain more obvious than it should, and there’s at least one confusing point that exposes even more issues with the plot. It’s not a bad start, but it’s certainly not perfect. If I were you, I’d wait until the next issue drops and check both at once to see if some of the holes get plugged… and if Symons and Robinson succumb to temptation and give Felicia a “bamf!” sound effect.

Podcast RSS Feed

Podcast RSS Feed iTunes

iTunes Google Play

Google Play Stitcher

Stitcher TuneIn Radio

TuneIn Radio Android

Android Miro Media Player

Miro Media Player Comics Podcast Network

Comics Podcast Network